(The Anatomical Theatre of Leiden, by Swanenburgh, 1616)

Over the years people with severed corpus callosums have taught us a lot about how our brains work. The c.c. is the part of the brain that connects the left hemisphere [the notoriously more analytic and linguistic part of the brain] with the right hemisphere [the part of the brain that handles emotions, images and intuition]. People whose two sides of their brains don’t talk to each other thus provide very useful information on how the two hemispheres are specialized. I was recently reading about a study for instance that had some very interesting implications for understanding the process of post-rationalization. In this particular study, conducted by Michael Gazzaniga of the University of California at Santa Barbara, a subject was shown the word ‘walk’ directly to his left eye, connected to the right hemisphere of the brain. Suddenly he got up and started to walk off. When asked why he had got up, he answered, ‘oh, I wanted to get a coke’. The left brain, which had seen the word, was incapable of producing any kind of justification, while the left brain, which had no idea about the command, was given the task of producing an explanation, and immediately did so. The subject fully believed his own story.

I find this weird and unnerving. It raises the possibility that maybe the part of me that I know best, the logical and linguistic side, is actually only making things up to cover the real intentions brewing in my right brain. Is this possible? Given this framework, it indeed could be that this ‘self’0 that I understand, that navigates life based on a series of logical and reasoned decisions, is actually a fabrication devised to ground whims that are in fact unbeknownst to me.

Which lends, does it not, an interesting aura to any discussion of zeitgeist, or any other residual meme of fate, religious determinacy, and the Hegelian Spirit? Think for instance of the visionary painter, following his instinct, creating masterpieces that seem to flow forth from him. Years later, people will look at the painting and see things moving in it which relate clearly to other aspects of culture and to cultural manifestations yet to emerge. In their spontaneous creation, artists often seem to be channelling something deep and important to their era, something that probably could not be articulated in a medium suited to analytic thought (such as the philosophical essay, for instance). Within this framework of hemispheres sketched above it is possible to conjecture that the painter’s right brain was in touch with a larger cultural ebb of non-verbal ‘information’, or maybe it’s better to say emotion, that his left brain was clueless about. Perhaps in addition to the dominant narratives through which understand our epoch there is a parallel non-verbal cloud into which we are also tapped, similar to a zeitgeist. I’m not presenting this in any way as the truth of the matter, but rather just pointing it out as an interesting way of thinking about things that is incidentally opened up by this bi-cameral model of cognition.

I am however interested in the utility of both image-creation and the discussion of images. In Bachelard’s introduction to his wonderful Poetics of Space, he says a couple of things that have stuck with me in this regard: first, that, ‘the poetic image places us at the origin of the speaking being’; and second, that, ‘poets and painters are born phenomenologists’ (a line that originates from Van den Berg). I think this is inspirational, and has inspired me increasingly to try to work with images in my own explorations. Perhaps this is a sign of an overactive left brain here, but for me this kind of talk provides a legitimation of image-play. For me these two observations of Bachelard’s open up image-play as a legitimate way of thinking.

Now maybe this sounds totally naïve, but I find it very useful to change my thinking around so that image-creation is a justified counterpart to analytical inquiry – to think that they could co-operate without one dominating the other. In the past, my love of art has often been centrally focused on what I could squeeze out of it: how many different ways I could think about it or how many different interpretations I could construct out of its material. The realization here is said better I think by Mark Kingwell when he comments that art ‘is never reducible to its mere propositional content – thinking so marks one of the ways we do violence to the aesthetic’ and continues to say that it ‘carries substance of a kind that could not be carried in any other way.’ [Opening Gambits, 2008] Thinking about art as the support of analytic inquiry or as somehow incomplete without it is to denude it of its rightful majesty and to deny that there is any sort of thought which cannot be expressed in the language of the philosopher, bureaucrat or scientist, which is just not true. Art doesn’t just serve thought, it is a form of thought.

Personally, I want in my approach to have a closer affinity to the artist than to the scientist. By this I mean that I wish to rely more heavily on internal rather than external observation. The artist (like the phenomenologist) believes in the usefulness of personal exploration – which of course requires a belief in the overlap of selves, a belief in the commonalities between us. The scientist, in contrast to this, relies on external observations of others to arrive at their conclusions about humanity. In this sense, in my work, I would like to take the stance of the artist and look within, in full recognition of my subjectivity, rather than review things from an ‘objective’ external observational standpoint.

Which is not to say that I reject that standpoint. I think the scientific method has produced and will continue to produce an absolutely astounding quantity of profound insight into our various human predicaments. As has the analysis of art, too. In fact one of the amazing things about art is I believe its capacity to provide for a wide diversity of thought. In fact as Kingwell has written elsewhere, ‘aesthetic success hinges on how much the work opens up, rather than closes down, the spaces of thought and wonder.’ [Monumental/Conceptual Architecture, 2004] In this sense art does in fact serve thought. It stimulates and encourages thought on a wide variety of important subjects.

Which all goes to explain why I am focusing much of my energy right now on the creation of images. The thesis document that I’m thinking of producing I hope to see as a sort of ‘table’, a bit like an operating table, but also like a coffee table. On this table I hope to place a series of images so that they can be seen in juxtaposition to one another and against a common background. I also hope to place narratives on this table, and myths, as well as facts gleaned from others’ scientific investigations. And then I’m going to mix all these things about, and flip them over each other and smash them into each other! And through these ‘table operations’, I hope to create a useful appraisal of my subject-matter that furthers our understanding of it and our capacity to act thoughtfully and intelligently with regard to it.

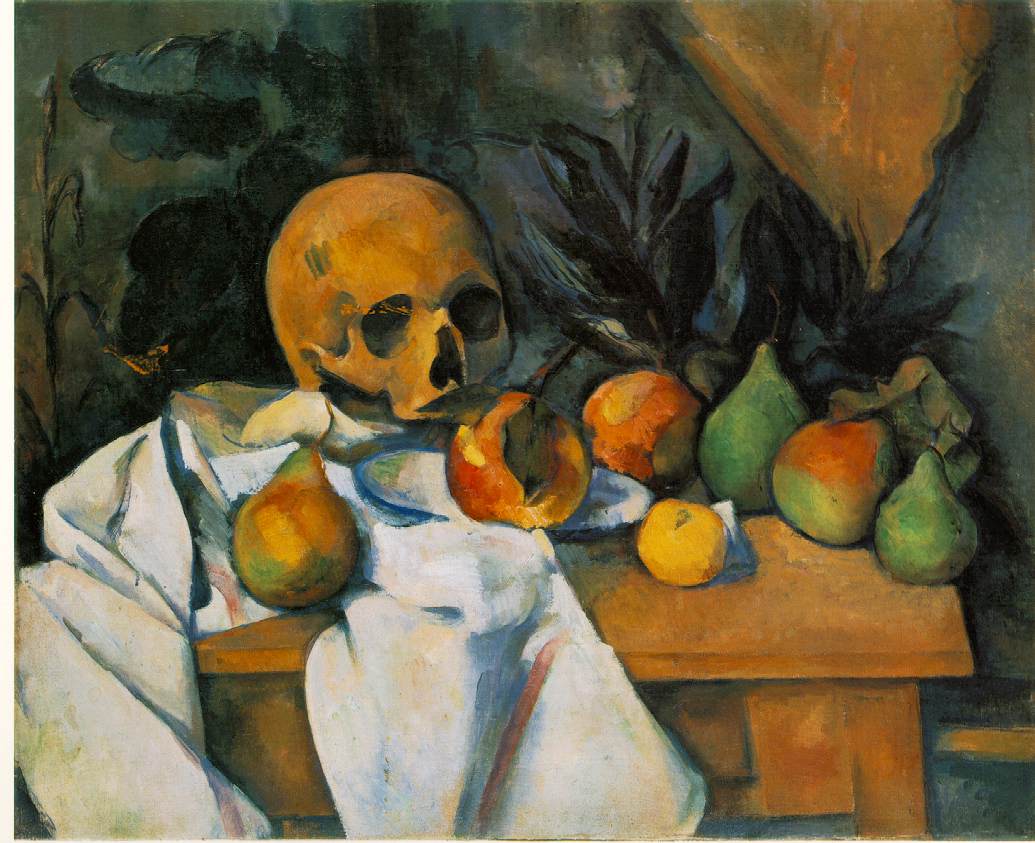

(Still Life With Skull, Paul Cezanne, 1895-1900)

No comments:

Post a Comment