Carl Gustav Jung, the famous Swiss psychologist, spent his entire life examining in intimate detail the complexities of the human condition. Although spurred by pressing issues of pathology and neurosis, his interest was ultimately in the intense questioning of what it means to be human. His lifelong study and wide-ranging research into the broad range of human experience makes him a compelling person for architects to study. What knowledge and insight, I wonder, can be distilled from the house that he built for himself?

Jung’s first important encounter with architecture as it relates to our psychology was in his interpretation of a dream that he had in 1909. In the dream he was in a house. Somehow instinctively knew that this was his house. He was on the upper storey at the beginning of the dream but became quickly curious about the levels below, and began to descend. As he descended, the house became progressively older and more primitive until eventually when he reached the basement he found himself in a dark, low cave. “Thick dust lay on the floor, and in the dust were scattered bones and broken pottery, like remains of a primitive culture,” he records in his auto biography. This dream was instrumental in the formulation of Jung’s model of the self. The house, he realized, was him. As he descended he moved through his various layers, from his conscious self to the unconscious, until eventually he reached the primitive remnants of his ancestors, that common inheritance which we all carry with us that he termed the ‘collective unconscious’.[1]

Years after this dream, about the time of his mother’s death in 1923, Jung decided to build himself a summer house . This home was to be, in his own words, “a kind of representation in stone of my innermost thoughts” and the work that he had been developing over his career. Words on paper were no longer enough for him; he felt a desire to build, to “make a confession of faith in stone”.[2] He developed this stone ‘confession’ over the next 12 years of his life.

His initial intention had been to build a small circular one-storey dwelling with “a hearth at the centre and bunks along the walls.” And it had to be near water. It was to be a simple structure, intended to frame a very simple life, a structure and a life both stripped down to their basic principles, the way that he had also stripped down the model of the psyche to its very basic form. He wished to have no electricity and no running water, chopping his own firewood for heat and cooking. “These simple acts make man more simple,” he wrote, “and how difficult it is to be simple!”

Indeed it seems like he did find it hard to be simple. Before even building the initial structure, Jung had to alter the initial plan to make it less ‘primitive’, and he then expanded it every 4 years for the next 12. First he built what he describes as a ‘tower-like annex’. Then, prompted by what he described as “a feeling of incompleteness”, he extended the annex in order to create a room for personal withdrawal. This was followed by the addition of a courtyard and ‘logia’ facing the lake, which was in turn followed, after the death of his wife, by an additional storey added to the original round structure at the centre of it all. If, as he saw it, that original round dwelling was him, raising it a second storey was and act of self-articulation, something he had felt afraid of doing while his wife was still alive.[3]

Jung intentionally aimed to bring into physical manifestation his idea of himself. Studying the tower he eventually built and the process that to him there gives us some insight into how this can be accomplished: how architecture can literally represent us. It is interesting that Jung chose to make this place for himself immediately following his mother’s death. It is as if he was prompted by the void that she left to fully assert himself in the form of a building. And this relationship between building and death goes further. When excavating in order to place the foundations, Jung uncovered a skeleton. A photograph of this skeleton is preserved in the tower. In addition, in the courtyard, Jung placed 3 stone tablets on which he chiselled the names of his paternal grandparents. All of these are sorts of momente mori, but also symbols of the past. Thus the past and future are both gathered in the present: the tower was built for the future, as most houses are, but it sprung out of his mother’s death and is filled with reminders of what has come before. And, in a way, the simplicity of the life inscribed by the tower is also an evocation of the past. As Jung writes in his autobiography, “in the tower at Bollingen it is as if one lived in many centuries simultaneously. The place will outlive me, and in its location and style it points backwards to things of long ago.”[4] Jung’s tower is thus a ‘locus’ of times: bringing together the past, present, and the future.

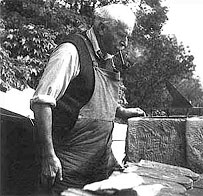

Detailed image of Bollingen courtyard, from http://rchrd.com/photo/archives/2006/01/cg_jungs_house.html

Detailed image of Bollingen courtyard, from http://rchrd.com/photo/archives/2006/01/cg_jungs_house.html