Although I don’t like it very much, I remain a very nostalgic person.

Nostalgia is, of course, complex. It is very rich in nuance and contains within it many forces that thus make it hard to pin down. This said, one of its defining aspects is, I believe, a longing for stasis. While rather embarrassed by this, I know that I am not alone in this longing. If I were, there would be no garden of Eden written into the Old Testament. If stasis were not so deeply attractive, the recurring image of a static paradise would not be so engrained in mythologies originating around the world. Indeed, neither ‘sustainability’ nor ecology would have such an emotional appeal, I think, without this common yearning. But I also know that there is no paradise, and I know that I will in fact die, and I know that the union of opposites will bring no mystical salvation. Acknowledging these things, my nostalgia emerges as a form of malady. I feel a bit better, however, at least knowing that it is a shared malady!

Tied as it is to the static, this very nostalgia often makes my relationship with technology a rather uneasy one. The word ‘technology’ as we so often use it is after all tied to innovation – it is new-making, the antithesis of stasis. Technology both changes and requires changing. The nostalgia I feel for a mythical paradisal stasis shudders at this.

But is it just technology that this nostalgia is at odds with or is there not maybe something bigger lurking behind it? Doesn’t capitalism also both constantly change and require changing? I think it is fair to say that it is actually in the service of consumer capitalism that technology is so prone to rapid and incessant change. In contrast to this, my nostalgia causes me to dream of an ecological image of carefully wrought stasis – very different from the economics upon which our consumer capitalism is based. While the image of an ecosystem is, in its idealized version, a closed system, our economies are open mouths that requiring feeding. They thirst for innovation, for newness, for ‘progress’. Ecology and economics, both images of the ‘house’ (ekos, greek root for house), are actually very different, despite their apparent similarity. Perhaps, then, the struggle that I feel with technology is actually to be found in the tension between these two images of the house.

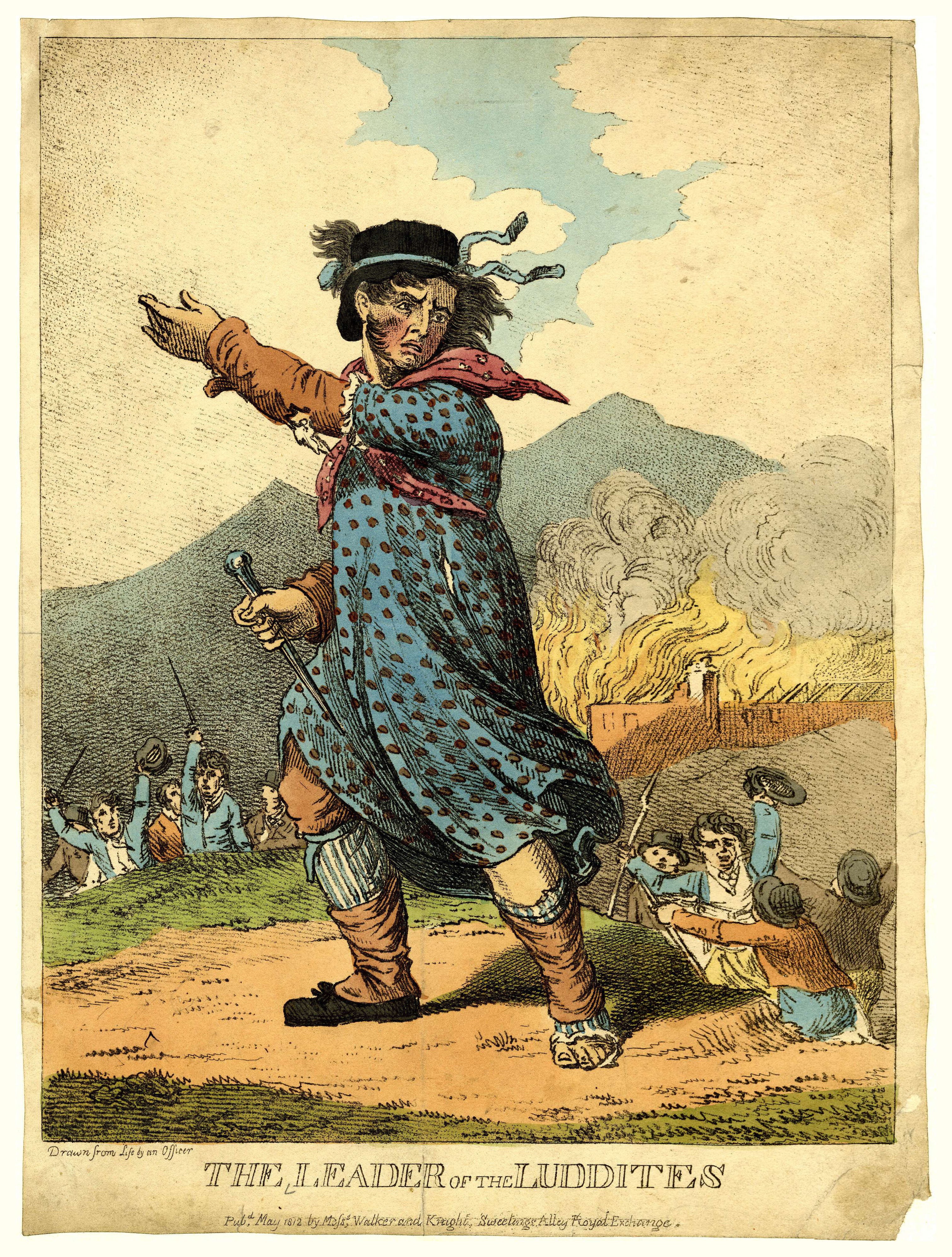

Indeed, then, I am a luddite. But I am not a luddite according to the sense that the word is commonly taken to have, rather I am a luddite in the traditional sense. The Luddite movement began in England in the early 1800s, taking its name from one Ned Ludd, a craftsman, who, according to lore, destroyed a number of mechanized looms in a fit of anger over the replacement of artisanal workers with machines. Ludd was not angry about technology per se. What he was angry about was the privileging of the abstract economic welfare of a corporation over the welfare of the individual. He was angry about how the craftsmen were being stripped of agency and reduced to proletarians, literally ‘reproducers’, who, as Jarvis Cocker famously described, have “nothing else to do” but “dance and drink and screw”.

It is in this sense that I would like to describe myself as a luddite – to whatever extent possible, I would like to remain conscious of the effects that technologies have on what it means to be human. To the extent that technology can increase our capacities for compassion, love, and aid our attempts at producing universal equality, then, well, I am all for it. Technology helps to feed the poor and aid the sick, it helps to bring empowerment to the underprivileged: in these senses who could fault it? As technology makes our use of resources more efficient it even has the ability to lighten our footprint on the earth.

It’s when I suspect our technology of serving the wrong purposes, of increasing the power of the powerful, of turning our footprint on the earth into a heavy bootstomp, of clouding our perception of injustice and our capacity for compassion . . . this is when I worry. I worry when I suspect technology of reducing ‘humans’ and ‘citizens’ to ‘users’. I worry when I suspect that much of our technology is a distraction from the important things of life and that it interferes with our ability to care both for each other and for the ecosystems in which we exist.

In the sense that I care a great deal more for humanity than I do for the translation of my will into phenomena, I am indeed a luddite. And although I recognize that my suspicions of technology are at least partially fuelled by nostalgia, I don’t think that that discredits them entirely. My hope is instead that the sort of conflict that arises out of this nostalgia has a degree of poetic potential to it, one that I may tap into.

Image at top is a picture inside of the Eden Project in the UK, from www.travelsinireland.com

Image of Ned Ludd taken from Wikimedia Commons it was published in 1812 as a publicity image

No comments:

Post a Comment