1.26.2009

On Cleaning

It felt good.

I have never read any of Henri Bosco’s novels, but his work is constantly referenced in Gaston Bachelard’s book, The Poetics of Space. In that text, Bachelard remarks on a passage of Bosco’s in which a housewife is cleaning an old house. She is polishing the wood, slowly, carefully, sensually. Bosco says of it that “this was the creation of an object,” or as Bachelard rephrases the sentiment, “the housewife awakens furniture that was asleep.” Creating, awakening: aren’t these beautiful ways to talk about cleaning? And that’s indeed how it felt to me, moving about my house with my dust rag and broom. It was as if shifting my care from object to object was at the very least an act of discovery if not creation. With my eyes and my hands I was exploring dimensions of the house that had hither-to been practically foreign to me, even if I saw them or was in contact with them everyday.

While Bachelard’s translator used the word housewife, I believe the more politically correct term is actually ‘home-maker’. This takes on an interesting additional level of depth in this context. While I always thought the phrase was a bit silly, seen in this light, I like it very much. I like to think of the home-maker transforming a house into a home through their care. I like to think of ‘care’ (in the sense of the sort of love that St Exupery alludes to in The Little Prince) as having that sort of power of metamorphosis. I like to think that care has the power to transform the world and even to connect us to it. Indeed, another way of speaking about this genesis of the world that takes place in care and attention, like how the housewife makes furniture by cleaning it, is by saying that care has the capacity to ground us existentially. Cleaning, in its requirement of close attention, repetitive movement, and, well, the slowing down that it asks of us, can really bring us into the present moment. It can, if we allow it, connect us to our place in time and space, a connection that can seem to get lost in the hurried business of our lives.

What Bachelard means when he likens the act of cleaning to making is that it makes it real for us. It brings it closer to us, and us closer to it. How often I’ve missed out on the potential of this kind of activity by rushing through a task. In the right frame of mind, as the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hahn has written, “even washing dishes after a big meal can be a joy.” I often just race through the process of scrubbing dishes, thinking about something else. Nhat Hahn actually recommends these sorts of tasks as meditational exercises.

And yet we’re constantly inventing machines to do these things for us, like the new breed of carpet cleaning robots. It is as if cleaning was somehow below us. I mean, as if vacuuming wasn’t already a pretty easy task, now you can buy a robotic device that will roam around your house, avoiding objects and pets with a built in sensor, cleaning up your dirt for you. Similarly, they’ve recently invented a robot that will clean your windows for you too. It’s a spider-like thing that suctions onto your window and moves around it, cleaning as it goes. These devices are primarily designed to save you time and effort which you could be expending on more important things. I mean, that’s the basic principle of the division of labour . . . if you can afford a cleaning robot, then your time and energy would be better spent on some other activity. I can’t help but feel though that in sacrificing daily activities we lose out on something important. Home-making, the phenomenal genesis of our home (our symbolic grounding-place), are we not also sacrificing this? In relying on these tools to do the work for us, are we not sacrificing an important aspect of our relationship with our home?

But pointing just at the tools here is a bit dishonest. The wedge driven between us and our environment by our disinterest in caring for it is only part of a larger problem. The cleaning machines are there to clear up time and effort for other purposes, in which case the question becomes how we actually spend our extra time and effort. Do we do something equally worthwhile? If we don’t, then the desire for these sorts of cleaning machines seems awfully like laziness. The immense rush forward often seems largely without a clear purpose.

Nhat Hahn’s take on Zen Buddhism offers guidance in reclaiming the mundane:

Washing dishes is at the same time a means and an end – that is, not only do we do the dishes in order to have clean dishes, we also do the dishes to live fully in each moment while washing them . . . we do not have to be swept along by circumstances. We are not just a leaf or a log in a rushing river. With awareness, each of our daily acts takes on a new meaning, and we discover that we are more than machines, that our activities are not just mindless repetitions.

While it is not necessary that our machines rob us of this awareness, the impulse that leads to the creation and acquisition of cleaning machines stands out starkly against Nhat Hahn’s comments, and I think it is a stark contrast that is worth noting.

If our cleaning of the floor is already mechanical – if we are elsewhere and our body is performing tasks rather than doing them – then there is little difference between this and a machine doing the cleaning for us. However, if we treated such ‘small’ tasks as somehow of existential importance, as Nhat Hahn and Bachelard would suggest, then we would truly lose out by letting a machine take over.

I Am A Nostalgic Luddite

Although I don’t like it very much, I remain a very nostalgic person.

Nostalgia is, of course, complex. It is very rich in nuance and contains within it many forces that thus make it hard to pin down. This said, one of its defining aspects is, I believe, a longing for stasis. While rather embarrassed by this, I know that I am not alone in this longing. If I were, there would be no garden of Eden written into the Old Testament. If stasis were not so deeply attractive, the recurring image of a static paradise would not be so engrained in mythologies originating around the world. Indeed, neither ‘sustainability’ nor ecology would have such an emotional appeal, I think, without this common yearning. But I also know that there is no paradise, and I know that I will in fact die, and I know that the union of opposites will bring no mystical salvation. Acknowledging these things, my nostalgia emerges as a form of malady. I feel a bit better, however, at least knowing that it is a shared malady!

Tied as it is to the static, this very nostalgia often makes my relationship with technology a rather uneasy one. The word ‘technology’ as we so often use it is after all tied to innovation – it is new-making, the antithesis of stasis. Technology both changes and requires changing. The nostalgia I feel for a mythical paradisal stasis shudders at this.

But is it just technology that this nostalgia is at odds with or is there not maybe something bigger lurking behind it? Doesn’t capitalism also both constantly change and require changing? I think it is fair to say that it is actually in the service of consumer capitalism that technology is so prone to rapid and incessant change. In contrast to this, my nostalgia causes me to dream of an ecological image of carefully wrought stasis – very different from the economics upon which our consumer capitalism is based. While the image of an ecosystem is, in its idealized version, a closed system, our economies are open mouths that requiring feeding. They thirst for innovation, for newness, for ‘progress’. Ecology and economics, both images of the ‘house’ (ekos, greek root for house), are actually very different, despite their apparent similarity. Perhaps, then, the struggle that I feel with technology is actually to be found in the tension between these two images of the house.

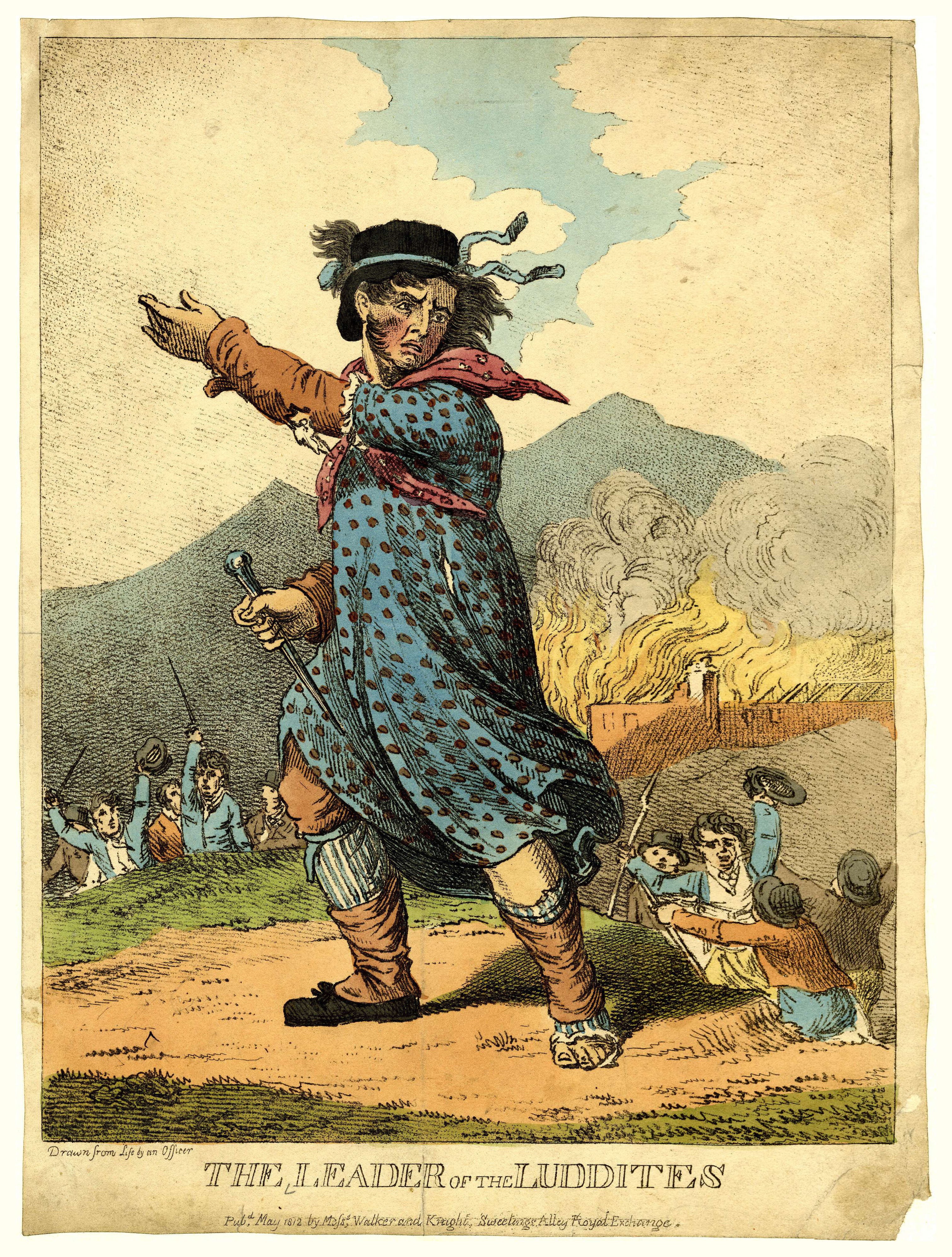

Indeed, then, I am a luddite. But I am not a luddite according to the sense that the word is commonly taken to have, rather I am a luddite in the traditional sense. The Luddite movement began in England in the early 1800s, taking its name from one Ned Ludd, a craftsman, who, according to lore, destroyed a number of mechanized looms in a fit of anger over the replacement of artisanal workers with machines. Ludd was not angry about technology per se. What he was angry about was the privileging of the abstract economic welfare of a corporation over the welfare of the individual. He was angry about how the craftsmen were being stripped of agency and reduced to proletarians, literally ‘reproducers’, who, as Jarvis Cocker famously described, have “nothing else to do” but “dance and drink and screw”.

It is in this sense that I would like to describe myself as a luddite – to whatever extent possible, I would like to remain conscious of the effects that technologies have on what it means to be human. To the extent that technology can increase our capacities for compassion, love, and aid our attempts at producing universal equality, then, well, I am all for it. Technology helps to feed the poor and aid the sick, it helps to bring empowerment to the underprivileged: in these senses who could fault it? As technology makes our use of resources more efficient it even has the ability to lighten our footprint on the earth.

It’s when I suspect our technology of serving the wrong purposes, of increasing the power of the powerful, of turning our footprint on the earth into a heavy bootstomp, of clouding our perception of injustice and our capacity for compassion . . . this is when I worry. I worry when I suspect technology of reducing ‘humans’ and ‘citizens’ to ‘users’. I worry when I suspect that much of our technology is a distraction from the important things of life and that it interferes with our ability to care both for each other and for the ecosystems in which we exist.

In the sense that I care a great deal more for humanity than I do for the translation of my will into phenomena, I am indeed a luddite. And although I recognize that my suspicions of technology are at least partially fuelled by nostalgia, I don’t think that that discredits them entirely. My hope is instead that the sort of conflict that arises out of this nostalgia has a degree of poetic potential to it, one that I may tap into.

Image at top is a picture inside of the Eden Project in the UK, from www.travelsinireland.com

Image of Ned Ludd taken from Wikimedia Commons it was published in 1812 as a publicity image

1.21.2009

3 Perspectival Foci on Consumer Technology

1. What are the impulses that drive the changes to our tools? Maybe immortality, dominance over the world, and power are driving forces, as well as sloth and greed. But maybe also we are driven by an altruistic will towards equality or an instinctive thirst for liberty? These also seem possible. What does it mean that the technology of tomorrow is actually fairly obvious to us today? Writing in the17th century, Bacon was able to predict the telephone and the submarine. What is it for instance about androids, arcologies, telepathy, flying cars, central computing networks, houses that respond to vocal commands, and teletransportation that are so attractive, for instance? Does technology have a telos?

2. How does technology enable and disable? What are its implicit hegemonies? How does the existing technology itself, rather than more important human concerns, drive the design and production of new technology? How do tools intended for one purpose inadvertently make demands of us that are unrelated, or disable certain activities and behaviours? What are the unintended consequences of technology?

3. If architecture is a form of technology, as we move forward, how will it begin to incorporate the changes taking place in other sorts of consumer technology? How will it incorporate accelerometers for instance, or RFID tags, or the availability of cheap digital display systems? Architects require some sensitivity in guiding these shifts. How do we mediate the negative consequences of the changes and encourage the positive consequences? If indeed huge changes are in the offing, how do we develop an ethic for guiding these changes?

1.19.2009

PATH / Capitalism / Technology / Death Denial

Across from me are two luggage stores. They are right next to one another, vying for our buying but selling two very different products – one high class stuff, the other very cheap and brightly coloured. A sign in one store declares “buy one get one 50% off”, the other, as if in desperate response, has a sign that says, “buy one get one ½ price!” This is pretty standard fare but the assumption is that if I know I’m getting a good deal, I will transcend my functional requirements in order to purchase a second piece of luggage. Oh come on! If I want one piece of luggage, I’ll buy one piece of luggage. But I’m sure it works, thus moving product, making room for more production, and lubricating the economy. Make more things! Sell more things! Keep the system going! The story is as old as it is revolting – in order for the division of labour that we have created to be effective, we need to keep producing luggage. We can’t just shut down the luggage factories once every person has a suitcase. We need people to keep buying things, an industrialized consumption to pair the industrialized production.

Fashion thus serves a very clear economic purpose. Desire and envy, covetousness and greed are manipulated and used in order to create the shifting mosaic of trends which keeps us buying more things. A belief in progress too drives this. If stuff is constantly getting ‘better’, then we are driven to keep buying the better stuff – if it doesn’t become untrendy, it soon be technically outdated, if it doesn’t fall apart first. One proposal to counteract this is to put the expired, “untrendy” back into the factory at the beginning of the cycle– thus the economic machine that we have created could in fact run perpetually and we would minimize the impact on the environment. There’s a good, if cynical, logic in that. But frankly I wonder to myself why we can’t just go in the opposite direction entirely and say, “when everyone has a good, strong suitcase, we will stop making more fucking suitcases!”?

What exactly is wrong with aiming for stasis damn it? But then again, maybe the perpetual production of new suitcases is kind of like aiming for stasis. Maybe the longing for a self-perpetuating economic system is in fact a denial of mortality. If everyone had a suitcase, for instance, it would open up the possibility of doing something entirely new. Perpetual suitcase manufacturing is a bit like navel-gazing – and very similar to pushing a rock up a hill only to find that the rock falls down every time! It’s running on a treadmill. Is the perpetuation of the suitcase making cycle because we can only think of slight variations on a theme? Or is it maybe a way of focusing on the present in order to forget our inevitable mortality? Are fashion, and, dare I say progress, distractions?

All this silliness with flash and technology, shifting trends that keep us racing around like greyhounds after a mechanical rabbit, is it only part of a big complicated device to ignore death? Technology indeed, very prone to quick changes in fashion, seems especially designed to break us free of death. Not only does it keep us focused on the small and the immediate, it also seeks to free us of our borders, to extend our will outwards into the world.

These people, rushing through, frantically typing into their Blackberrys, miles away from the people immediately around them, do they often think about death? Is this infinite world, with its crushing unanswerable questions and its immense depths of passion and misery, is it real to them?

1.03.2009

6 Characteristics of the New Technology

In my musings recently I have been struggling with an over- use of the ambiguous word ‘technology’. Technology of course can mean any artefact produced by humanity with an instrumental purpose. But when I’m talking about the new technology, I’m usually not talking about new types of window blinds. When I speak about new technology, what I am in fact referring to is electronic and digital technology – the laptop on which I’m writing this, the Internet on which you are reading this, etc. As a further attempt at clarification, though, I’ve cobbled together the following list of trends that define technology that I am interested in:

1. The Disintegrating Interface – the desire to have a direct response to will is causing an erosion of our interfaces with technology– the delay between will and phenomena is an annoyance and people want to breakdown the physical barriers causing this delay.

2. Miniaturization – closely related to the erosion of the interface is the miniaturization of technology – technology tends to get more and more powerful and the electronic devices that we use thus, instep with this, become smaller and smaller.

3. Wirelessness – this is another aspect in addition to miniaturization that increases our mobility, while also increasing our constant interaction with the technology and the attached networks.

4. Networked – simultaneous to our closer and more constant interaction with our tools, our tools are becoming increasingly tied up in vast series of networks.

5. Simultaneity – Communications technology allows for a new simultaneity – a new universal time. Our understanding of space-time is completely revamped.

6. Simulation / Repetition – Our tools give us the power to record and mimic things around us. I can, using code, make an informational model of the room that I am currently sitting in. One of the key aspects of information is of course that it is quantifiable, and because it is quantifiable it can be reproduced infinitely. Thus the room that I am in, once simulated is easily repeatable. Similarly, if I was to upload myself onto a computer (reinvent myself purely as information) then there could easily be two me’s, or three, or 72. This ability to simulate and repeat is a key characteristic of digital technology.