12.25.2008

More on Interface Blending

Disintegration of the Interface

Frankly I find the images pretty uncomfortable, but that's part of what I find fascinating about the subject matter.

12.16.2008

Architecture as Law

To what extent may the physical construction of the world we inhabit constrain our actions, similar to law?

It is often said that architecture gives form to life. This occurs both by crystallizing our values in form, and also in the canalization of our activity. For an example of the first you need reach no further than any monumental architecture, be it the temples of ancient Rome or the courthouses and parliaments of the 19th and 20th centuries. The second way in which architecture controls is more subtle. For an example, think about the difference between a 19th century compartmentalized house and a late 20th century ‘open-plan’ house: the Victorian house is far more prescriptive in how it is used – it controls your use of the house by literally guiding your body through it.

In Lawrence Lessig’s book, Code (1999), in which he attempts to demonstrate how the construction of the Internet subtly, and sometimes not-so-subtly, controls our use of it, he references architecture’s operational affinity to law parenthetically as a sort of proof by analogy. He offers several examples. Robert Moses’ bridges to Long Island were intentionally built too short to allow buses (and thus ‘undesirables’) through. Speed bumps demand (more or less effectively) a certain type of behaviour from people, thus enforcing the will of the ‘designer’. Locked doors, of course, are an obvious and simple example of controlling access, as are guard rails, etc. These are all examples of architecture operating as a sort of law – exacting a certain behaviour from people through the design of the physical environment.

Examples like the speed bumps and the bridges are of course only architecture in an expanded sense of the word, but can we not imagine similarly a floor surface designed to make people walk slower (of foam maybe?), or a door that was very small and thus only allowed a certain dimension of person through! We could also imagine a chair that only fit a certain size of hip. If you were not the right shape, you would be “architecturally” prevented from sitting in the chair. Although this sounds fanciful, it happens on a regular basis. Chairs are always designed for a specific range of the population. Think of seats at the cinema– they’re all the same size, but we aren’t. A very short person can’t see over the seat in front of them – a very large person won’t fit between the arm-rests. Benches are great largely because of their flexibility – you can sit, or sprawl, or lie down. One person could use a bench, or several – and it doesn’t matter the size of your rear end. But many public benches now have small ‘nubbins’ on them that are there specifically to prevent you from lying down. The design of these benches is at the service of the authorities, operating as a form of law.

But there is another example of chairs operating in this way which is less obvious: think of Corb’s ergonomically-designed seat in the bathroom of Villa Savoye. In that this seat is specifically designed to match a person’s body, in its very ‘humanistic’ customization, it is actually exclusionary! This observation, that customization has the capacity to be exclusionary, opens up a very interesting question. Could humanism in architecture, and I’m thinking specifically here of the ‘phenomenological’ approach propagated by Holl and Pallasmaa amongst others, not actually be dangerous in its very specificity? The double-edged blade of phenomenology is that it by necessity is highly personal, and thus has the danger of being both narcissistic and exclusionary. The power of the search for the ‘things-in-themselves’ lies in its situation in experience, but that experience is always personal. This sort of design has the capacity to be exclusionary in the same way in which the philosopher Albrecht Wellmer has spoken about the impulse towards ‘regional’ styles in architecture. This sort of neo-conservative thinking about territory, he has pointed out, while strengthening inclusion and ‘grounding’, simultaneously excludes. In the same way that Moses’ bridges prevented certain people from getting to Long Island, does regionally-styled architecture not exclude those who, by virtue of geographical origin, don’t ‘get it’?

Security cameras too are a form of architecture acting as law, and not because of their actual use to record things. Security cameras in reality serve primarily a symbolic function, as everyone knows: reminding would-be offenders of the powers that be. They are almost a form of ornamentation, iconographically representing the power of the nation state (or corporation) just as statues of angels and demons used to remind us of the powers of good and evil.

Which of course brings us to Jeremy Bentham, the great Utilitarian philosopher, and his famous excursion into architecture. The genius and effectiveness of Bentham’s single (as far as I know) architectural foray, the Panopticon, continues to strike terror into the hearts of theoreticians of architecture to this day. It symbolizes the power of architecture, in the service of authority (as it always is, don’t forget), to reduce people through fear, to humiliate and tame them through exposure.

plan of panopticon by J. Bentham, from wikimedia commons

Architects like to speak rhapsodically (and hubritically) of their power to influence people through architecture. There is an enduring belief in the field that architecture can change the world, the lurking spectre of a modernist idealism that is not yet spent. Architecture can indeed, as Lessig points out, operate as a sort of law. And in the same way that it disables a fat person from using a narrow door, it can enable a person who has lost the use of their legs to enter and explore a museum. Ramps and elevators help people with disabilities get around buildings. Railings prevent people from falling off of balconies. Small bumps on walls allow people without the use of their vision to locate certain rooms. But there is a darker side to all of this as well. Regionalistic architecture includes those that belong, but potentially excludes outsiders. Gothic churches both inspired hope and struck fear into the hearts of the faithful. Humanistic architecture implies a definition of humanity. Ornamental security cameras both reassure people and reinforce the power of an abstract and dis-embodied authority.

12.12.2008

PATH Redux

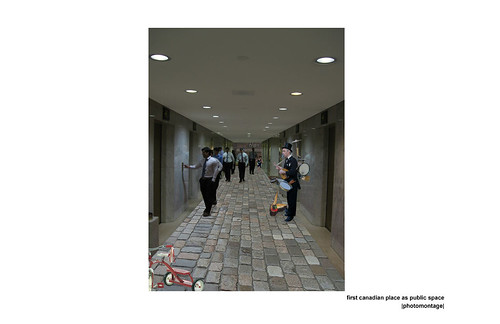

Spacing Magazine recently ran a competition called ThinkToronto in which young designers were asked to present their vision for some aspect of Toronto's future. Now that I know for absolutely sure that my design was not selected (the names were officially announced on Wednesday) I feel I can post it here.

The text interspersed with the images is the text that I submitted with the competition. In retrospect I realize that it probably sounds a bit radical. This is a different breed of project from those that actually won the competition, both in its criticality and in its lack of refinement.

All the images appear to be getting cut off - so if you're interested please click on them to see them in full.

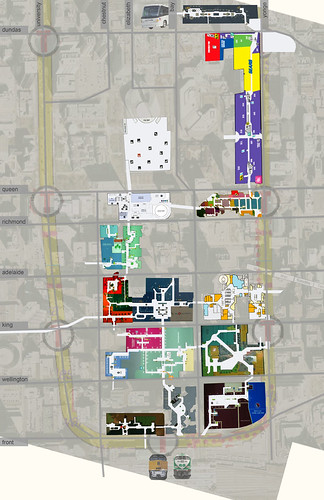

** collage diagram showing current configuration

Healthy democracies derive their strength and flexibility from an active and dynamic public sphere. This kind of public sphere finds its clearest manifestation in the sort of public space that allows for free encounters and dialogue between citizens. This project entails a radical rethinking of the PATH system as a new subterranean network of public space, one that allows for collisions of difference – engagement between citizens from all segments of society, unfettered by the homogenizing pressures of consumerism.

This proposal creates a new zone in the city where people want to go, and can go year-round, not only to shop, but to be: to relax, to talk, to engage politically, to engage culturally, to perform and to spectate, to exercise their bodies, and to expand, focus, problematize, and engage their minds.

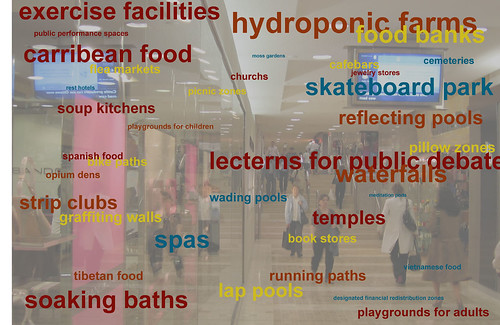

** diagram showing some possible programs that could be associated with the PATH

The current configuration of PATH is predicated upon and supports a limited and exclusionary vision of what it means to be human. The new PATH operates outside of this paradigm, inviting citizens to display openly their stories, traditions, habits and beliefs, and offering new possibilities for experiencing difference -- a key building block in constructing a tolerant, pluralistic society. Public space is about this sort of engagement. A redefinition of PATH would provide a massive infusion of viable public space, usable throughout the year, into the heart of downtown Toronto.

As a first step, the City of Toronto is required to expropriate a large portion of PATH. Although extensive, this expropriation is confined to the connective tissues that currently link the commercial enterprises. Not performing this acquisition would be equivalent to trying to plan a city in which not only the buildings but the sidewalks, the roads, and the parks were all owned by private companies. The expropriation is thus necessary in order to implement a comprehensive subterranean urban plan.

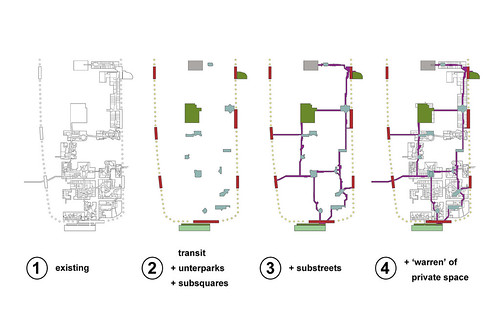

** Maps showing existing conditions and interventions

As primary nodes in this new subterranean urbanism, a handful of undergrade parks, or ‘unterparks’, are to be established. Three suitable candidates for this purpose are immediately apparent: the parking garage under Nathan Philips Square, the parking garage under Yonge-Dundas Square, and the ‘moat’ that lies between Union Station and the adjacent subway station. The future for which this PATH is envisioned is one without the need for cars in the downtown core. Unterparks are large, diverse zones including market-spaces, exercise spaces, skateboard parks, moss gardens, community pools, etc. In the cases of both the current parking lots deep incisions are necessary to allow natural light in. At Nathan Philips Square, for instance, the reflecting pool could become a waterfall with water streaming down into another pool below.

After the unterparks, a series of smaller public spaces are to be established, called ‘subsquares’. These are mainly repurposed from existing foodcourts, but are significantly redefined. Instead of fast food chains, affordable restaurants and cafés are encouraged with individual seating. Subsquares are places to meet, to rest, to enjoy the performance of a busker, or to have a picnic on the steps of a fountain.

The third element of expropriation is then to establish a clear network of underground boulevards, or ‘substreets’. The substreets will provide connections between the unterparks, the subsquares and the primary transit nodes. These are pedestrian promenades, both intended to channel commuters to and from their places of work, but also for people to generally enjoy walking along – to see and be seen, not like the Ramblas of Barcelona. The proposed substreets are considerably wider than most of the current corridors in PATH. Generally they are to be eight to twelve metres wide, allowing both for a generous thoroughfare for pedestrians and also room for street furniture on the side.

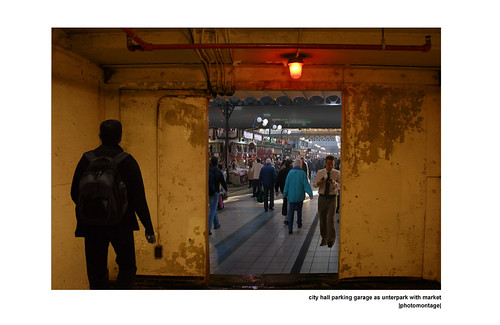

** Nathan Philip Square parking garage becomes a market, with perforations above to introduce light

Beyond these acts of expropriation, the remainder of the PATH shall continue to be privately owned, including all of the retail space off of the primary public areas. Generally, however, it is recommended that the current owners sell the retail units as condominium units, so that tenants may own the property instead of just renting. This will increase the diversity of shops and programme available in PATH.

Some simple strategies for increasing the likeliness of direct public encounter and dialogue include ‘graffiting walls’ and public stages and lecterns. Graffiting walls are chalk-board walls complete with chalk where people are encouraged to air their issues and grievances, in the manner of the medieval ‘talking statues’ of Rome or also in the manner of bathroom graffiti. The public stages and lecterns are to be used for speeches and public debates like ‘speaker’s corner’ in London but also they are to be used as stages for both impromptu and organized performances.

** Cut away perspective image demonstrating some potential moments from the proposed new PATH